Post by Babu Baboon on Sept 2, 2020 14:45:00 GMT -6

via the Saturday Evening Post

Let’s face it; people fall for hoaxes. Whether it’s sideshow mermaids or Sasquatch footprints or Satanic rings of human traffickers operating out of pizza restaurants, some people will believe anything. It’s even worse when the source of the hoax is a regular, everyday news source. That was the case in August of 1835 when the New York Sun newspaper kicked off an elaborate multi-part hoax that convinced people that cities, rivers, and, well, man-bats, could all be found on The Moon. It’s called the Great Moon Hoax, and this is how they sold it.

A good hoax should contain an element of truth, and the first thing that the initial article did was try to establish credibility by linking it to Sir John Herschel. Herschel was one of those incredibly talented minds who worked across a variety of disciplines. In addition to being an astronomer, a chemist, and a mathematician, he dabbled in botany and photography. He also invented the blueprint (that’s right; blueprints have an inventor, and it’s John Herschel). It ran in the family; his father discovered Uranus, and the younger Herschel named four moons of that planet and seven moons of Saturn. He built his own telescopes, helped figure out the cause of astigmatism, made models of lunar craters, and even co-founded the Royal Astronomical Society (in 1820). With Herschel being such a widely known expert, any discoveries attributed to him would carry an air of truth. The fact is that Herschel had no idea that his name was going to be appropriated for a long con.

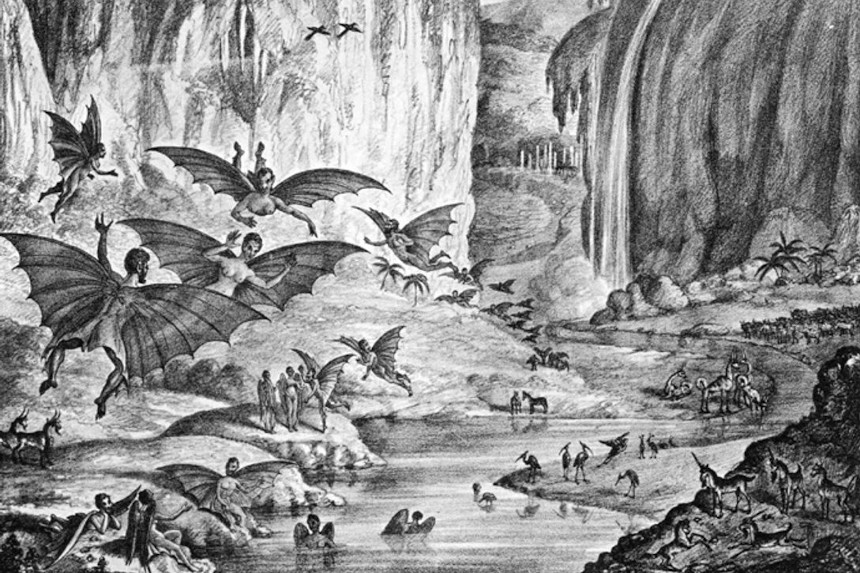

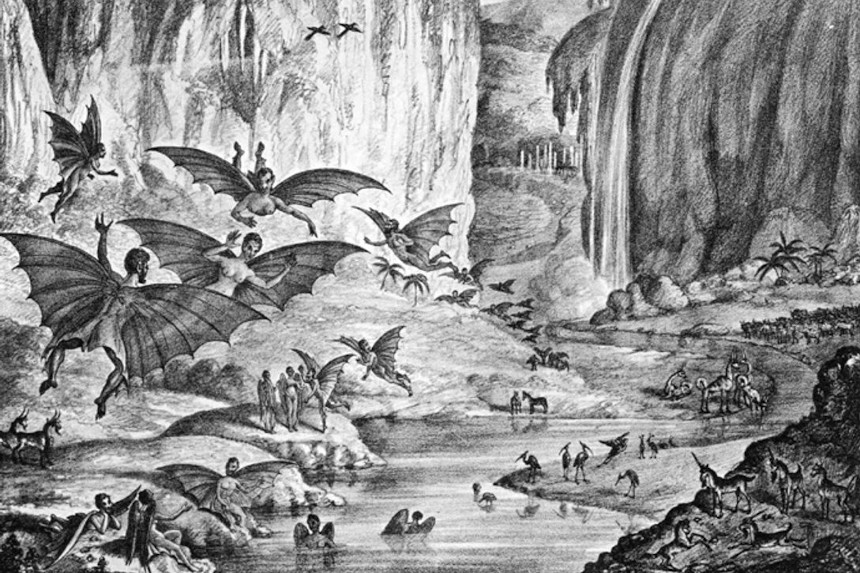

A illustrated depiction of the "ruby amphitheater" as it was described in the New York Sun

One of the lithographs that ran with the multi-part New York Sun series, which depicted the moon teeming with life. (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain in the United States)

The first hint that the story was coming arrived in the form of an ad that ran on August 21. The ad promised that a purported story from The Edinburgh Courant would run in the Sun. When the first story landed on August 25, it did so with the headline “GREAT ASTRONOMICAL DISCOVERIES LATELY MADE BY SIR JOHN HERSCHEL, L.L.D. F.R.S. &c. At the Cape of Good Hope [From Supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science.]” Using the Cape of Good Hope was another clever bit, as that location in South Africa was home to the Royal Observatory, lending some more verisimilitude to the story. The stories themselves carried the byline of Dr. Andrew Grant, who traveled with Herschel and documented his observations. Of course, Grant didn’t exist.

The six articles composed a narrative that had the Moon teeming with life, with some species identical to Earth’s and some vastly different. For every goat or bison, you had unicorns and tailless beavers that walked upright. The article described creatures with a human appearance but bat-like wings, even assigning them the scientific name Vespertilio-homo (Vespertilio is a genus of bats, also known as vesper or frosted bats; vesper itself was a Latin word for “evening”). The man-bats supposedly built temple-like structures on the surface of the Moon. The ability to make such precise discoveries and observations was owed to a new telescope that Herschel had built, which, coincidentally, was destroyed after all of the discoveries were made because sunlight through the powerful lens set the observatory building on fire. Lithographs were created to illustrate the pieces; in some you can see bat-men, unicorns, palm trees, and more, all suggesting a strange world right above us in the sky. The immediate effect for the Sun is that circulation shot up; articles over time have suggested that rumors of impossibly high numbers were exaggerated, but it’s fair to say that the increased numbers allowed the paper to thrive in a tough market, thanks to the Moon articles.

And, of course, it was a total fraud. Though there have been insinuations that other people were involved, the genesis of the Great Moon Hoax leads back to one man, Sun writer Richard Adams Locke. Locke was trying to achieve two goals. The first? Sell more papers. The second? That was deeply rooted in some of the culture of the time. Locke was satirizing scientific and religious personalities who were making grand, unprovable statements about the solar system and presenting them as fact. One example was “Discovery of Many Distinct Traces of Lunar Inhabitants, Especially of One of Their Colossal Buildings,” a paper presented in 1824 by astronomer Franz von Paula Gruithuisen. While Gruithuisen did accurately guess that lunar craters were caused by impacts, his suggestion of cities and jungles on the Moon were shot down by observers with better telescopes.

Another target of Locke was likely Reverend Thomas Dick, author of The Christian Philosopher. While Dick lobbied for the idea that science and religion could peacefully co-exist and advocated the abolition of slavery, he also made outlandish guesses as to the population of the solar system. He claimed to have mathematically determined that 21.9 trillion people lived in the solar system, and that the Moon had a population in excess of 4 billion; his basis for this was simply applying the population density of England to the projected sizes of the other planets. It should be noted that Dick was from Scotland, and that the original teaser ad suggesting that the Moon story originated in The Edinburg Courant may have been a sly joke.

As the “Great Moon Hoax” spread, some people took it seriously, and some people took it for a joke. When it was revealed as a hoax several weeks later, the paper never reprinted a retraction. Sir Herschel found the whole thing quite funny at first, but later grew tired of having to answer questions about it. Someone who wasn’t amused by the whole affair was Edgar Allan Poe. That’s because Poe claimed that the Moon Hoax story wasn’t just an invention; it was plagiarism. His allegation was based on the fact that he’d written a very similar type of story (fictional, for his part) that ran two months earlier in the Southern Literary Messenger. The title was “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” and the editor of the piece was . . . Richard Adams Locke.

Poe’s story was supposed to be — wait for it — a hoax itself. It was also supposed to run in multiple installments. The tale centers on a man who goes to the Moon in a balloon with a device that manufactures breathable air. However, Poe discontinued the story after having his thunder stolen by the Sun pieces. And then he planned his revenge (he was, after all, Edgar Allen Poe). In 1844, Poe published a story reporting that balloonist Monck Mason had crossed the Atlantic in three days using a gas balloon. The story was a sensation, but it was deflated two days later when it was revealed that Poe’s story was itself a hoax, and that he’d done it to burn the Sun and his editor on the balloon story . . . Richard Adams Locke. Angry that the Sun had profited from his ideas but he never saw a cent, Poe took the opportunity nine years later to make the paper and Locke both regret it. Matthew Goodman’s 2008 book The Sun and The Moon relates the tale behind Poe, Locke, the Sun articles, and Poe’s piece, which is now known as “The Balloon-Hoax.” One lasting effect of the Moon/Balloon back-and-forth was that it inspired Jules Verne twice. The French novelist, widely considered one of the most important figures in science fiction, mentions both the Great Moon Hoax and Poe’s original story in 1865’s From the Earth to the Moon. Additionally, Poe’s balloon story piqued his interest in that method of travel, something that he includes in both Around the World in 80 Days and Five Weeks in a Balloon.

Looking back, the Great Moon Hoax manages to be both believable and unbelievable. It seems odd that a writer would put the reputation of their paper at risk to sell copies based on a completely fictional story. In the case of Locke and the Sun, the gamble worked. You could say that it’s odd that people believed it at all, but history has shown that people are willing to believe quite a lot, even in the face of significant evidence. It’s funny to think that the Sun Moon battle would be so relatable to our current social and technological issues, but Jules Verne probably wouldn’t be surprised at all.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain in the United States

Let’s face it; people fall for hoaxes. Whether it’s sideshow mermaids or Sasquatch footprints or Satanic rings of human traffickers operating out of pizza restaurants, some people will believe anything. It’s even worse when the source of the hoax is a regular, everyday news source. That was the case in August of 1835 when the New York Sun newspaper kicked off an elaborate multi-part hoax that convinced people that cities, rivers, and, well, man-bats, could all be found on The Moon. It’s called the Great Moon Hoax, and this is how they sold it.

A good hoax should contain an element of truth, and the first thing that the initial article did was try to establish credibility by linking it to Sir John Herschel. Herschel was one of those incredibly talented minds who worked across a variety of disciplines. In addition to being an astronomer, a chemist, and a mathematician, he dabbled in botany and photography. He also invented the blueprint (that’s right; blueprints have an inventor, and it’s John Herschel). It ran in the family; his father discovered Uranus, and the younger Herschel named four moons of that planet and seven moons of Saturn. He built his own telescopes, helped figure out the cause of astigmatism, made models of lunar craters, and even co-founded the Royal Astronomical Society (in 1820). With Herschel being such a widely known expert, any discoveries attributed to him would carry an air of truth. The fact is that Herschel had no idea that his name was going to be appropriated for a long con.

A illustrated depiction of the "ruby amphitheater" as it was described in the New York Sun

One of the lithographs that ran with the multi-part New York Sun series, which depicted the moon teeming with life. (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain in the United States)

The first hint that the story was coming arrived in the form of an ad that ran on August 21. The ad promised that a purported story from The Edinburgh Courant would run in the Sun. When the first story landed on August 25, it did so with the headline “GREAT ASTRONOMICAL DISCOVERIES LATELY MADE BY SIR JOHN HERSCHEL, L.L.D. F.R.S. &c. At the Cape of Good Hope [From Supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science.]” Using the Cape of Good Hope was another clever bit, as that location in South Africa was home to the Royal Observatory, lending some more verisimilitude to the story. The stories themselves carried the byline of Dr. Andrew Grant, who traveled with Herschel and documented his observations. Of course, Grant didn’t exist.

The six articles composed a narrative that had the Moon teeming with life, with some species identical to Earth’s and some vastly different. For every goat or bison, you had unicorns and tailless beavers that walked upright. The article described creatures with a human appearance but bat-like wings, even assigning them the scientific name Vespertilio-homo (Vespertilio is a genus of bats, also known as vesper or frosted bats; vesper itself was a Latin word for “evening”). The man-bats supposedly built temple-like structures on the surface of the Moon. The ability to make such precise discoveries and observations was owed to a new telescope that Herschel had built, which, coincidentally, was destroyed after all of the discoveries were made because sunlight through the powerful lens set the observatory building on fire. Lithographs were created to illustrate the pieces; in some you can see bat-men, unicorns, palm trees, and more, all suggesting a strange world right above us in the sky. The immediate effect for the Sun is that circulation shot up; articles over time have suggested that rumors of impossibly high numbers were exaggerated, but it’s fair to say that the increased numbers allowed the paper to thrive in a tough market, thanks to the Moon articles.

And, of course, it was a total fraud. Though there have been insinuations that other people were involved, the genesis of the Great Moon Hoax leads back to one man, Sun writer Richard Adams Locke. Locke was trying to achieve two goals. The first? Sell more papers. The second? That was deeply rooted in some of the culture of the time. Locke was satirizing scientific and religious personalities who were making grand, unprovable statements about the solar system and presenting them as fact. One example was “Discovery of Many Distinct Traces of Lunar Inhabitants, Especially of One of Their Colossal Buildings,” a paper presented in 1824 by astronomer Franz von Paula Gruithuisen. While Gruithuisen did accurately guess that lunar craters were caused by impacts, his suggestion of cities and jungles on the Moon were shot down by observers with better telescopes.

Another target of Locke was likely Reverend Thomas Dick, author of The Christian Philosopher. While Dick lobbied for the idea that science and religion could peacefully co-exist and advocated the abolition of slavery, he also made outlandish guesses as to the population of the solar system. He claimed to have mathematically determined that 21.9 trillion people lived in the solar system, and that the Moon had a population in excess of 4 billion; his basis for this was simply applying the population density of England to the projected sizes of the other planets. It should be noted that Dick was from Scotland, and that the original teaser ad suggesting that the Moon story originated in The Edinburg Courant may have been a sly joke.

As the “Great Moon Hoax” spread, some people took it seriously, and some people took it for a joke. When it was revealed as a hoax several weeks later, the paper never reprinted a retraction. Sir Herschel found the whole thing quite funny at first, but later grew tired of having to answer questions about it. Someone who wasn’t amused by the whole affair was Edgar Allan Poe. That’s because Poe claimed that the Moon Hoax story wasn’t just an invention; it was plagiarism. His allegation was based on the fact that he’d written a very similar type of story (fictional, for his part) that ran two months earlier in the Southern Literary Messenger. The title was “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” and the editor of the piece was . . . Richard Adams Locke.

Poe’s story was supposed to be — wait for it — a hoax itself. It was also supposed to run in multiple installments. The tale centers on a man who goes to the Moon in a balloon with a device that manufactures breathable air. However, Poe discontinued the story after having his thunder stolen by the Sun pieces. And then he planned his revenge (he was, after all, Edgar Allen Poe). In 1844, Poe published a story reporting that balloonist Monck Mason had crossed the Atlantic in three days using a gas balloon. The story was a sensation, but it was deflated two days later when it was revealed that Poe’s story was itself a hoax, and that he’d done it to burn the Sun and his editor on the balloon story . . . Richard Adams Locke. Angry that the Sun had profited from his ideas but he never saw a cent, Poe took the opportunity nine years later to make the paper and Locke both regret it. Matthew Goodman’s 2008 book The Sun and The Moon relates the tale behind Poe, Locke, the Sun articles, and Poe’s piece, which is now known as “The Balloon-Hoax.” One lasting effect of the Moon/Balloon back-and-forth was that it inspired Jules Verne twice. The French novelist, widely considered one of the most important figures in science fiction, mentions both the Great Moon Hoax and Poe’s original story in 1865’s From the Earth to the Moon. Additionally, Poe’s balloon story piqued his interest in that method of travel, something that he includes in both Around the World in 80 Days and Five Weeks in a Balloon.

Looking back, the Great Moon Hoax manages to be both believable and unbelievable. It seems odd that a writer would put the reputation of their paper at risk to sell copies based on a completely fictional story. In the case of Locke and the Sun, the gamble worked. You could say that it’s odd that people believed it at all, but history has shown that people are willing to believe quite a lot, even in the face of significant evidence. It’s funny to think that the Sun Moon battle would be so relatable to our current social and technological issues, but Jules Verne probably wouldn’t be surprised at all.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain in the United States